AI-Driven Application & Process Testing: Embracing Agentic Testing

Learn how Agentic AI enables digital transformation, delivering true hyperautomation.

Implementing the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz) is a priority for companies right now. Planning a step further shows that it is worth laying the foundations now for a deeper integration of sustainability principles in the supply chain.

With the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz, or Lieferkettengesetz for short) at the latest, there is movement on the issue of social and environmental sustainability in supply chains, and companies need to address this field strategically and proactively: Robust implementation of risk management and reporting requirements from the German Supply Chain Due Diligence act must be quickly followed by deeply embedding sustainability in supply chain processes and support through technology and automation.

The sustainable and socially responsible transformation of supply chains is both a necessity and a massive challenge for companies. Systematic implementation requires several points: increased transparency about the origin of products, integration of clear standards into purchasing and management processes, active risk management to identify potential violations of prohibitions and obligations, and systematic implementation of preventive and remedial measures.

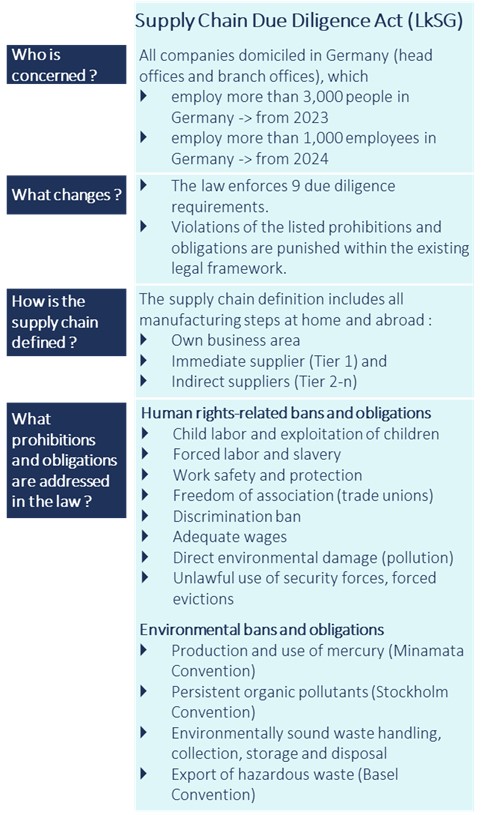

Following France’s law of 2017, and preceding upcoming EU regulation likely this year, the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (German official abbreviation LkSG, here Supply Chain Act) of June 2021 takes a step in this direction. Setting a new international benchmark, the act provides a binding description of the due diligence obligations of German companies on social compatibility and sustainability in end-to-end supply chains, “from the extraction of raw materials to delivery to the end customer”. The law does not differentiate between industries or stages of the value chain and thus applies equally to all companies (Fig. 1).

One value of due diligence requirements is that they enforce the observance of human rights in global supply chains by law. But this is only a first step towards holistic sustainability. That is why preparations for implementing the Supply Chain Act should keep an eye on the medium- to long-term perspective of transforming supply chains in a socially and environmentally responsible way. After all, the important step of mandatory risk management must be followed by further steps. Deep, automated embedding of human rights and environmental aspects in purchasing processes and the structural realignment of supply chain strategies must become the focus of further strategic development.

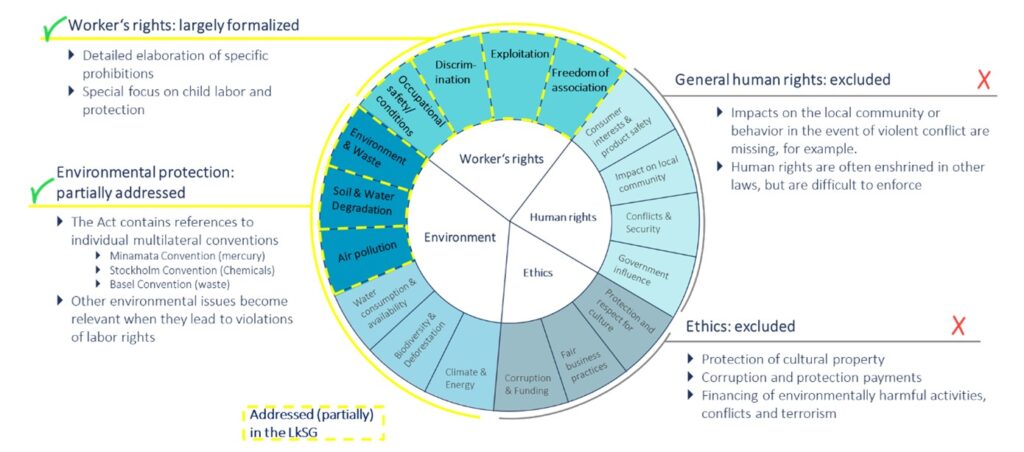

The Supply Chain Act formalizes handling of internationally recognized prohibitions and obligations, labor-relevant rights within the UN Human Rights Charter, and the labor rights of the International Labor Organization. Violations of these prohibitions and obligations occurring abroad are made legally enforceable in Germany. The protection of children is given overriding importance, but other labor rights are also listed in the law.

Environmental pollution is addressed insofar as it leads directly to the violation of human rights. Violations of multilateral agreements on the prevention of environmental damage with mercury, chemicals and waste can also be punished with the new law.

However, relevant components of a triple bottom line (people, planet, profit) were left out of the text. For example, while individual environmental protection issues are formalized in the Supply Chain Act, central issues such as climate protection are not. Regarding human rights, only obligations that are directly related to labor rights are covered. However, general human rights and ethics are excluded (Fig. 2). Due to their social and economic relevance, these dimensions must not be neglected by companies.

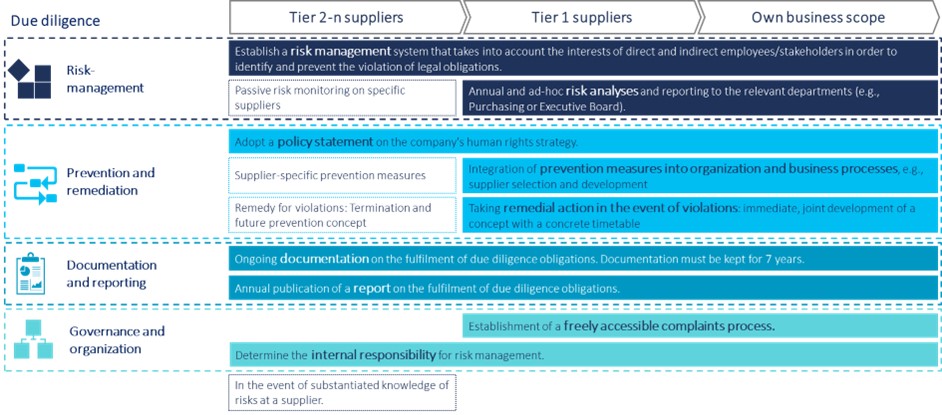

As a direct consequence of the new law, affected companies must comply with nine due diligence obligations (Fig. 3). These begin with a policy statement at the highest management level regarding the company’s human rights strategy. A risk management system is required, for which responsibility must be defined at an appropriate place in the organization. The risk management system must be set up in such a way that human rights and environmental risks can be continuously monitored, and violations prevented or eliminated. Annual and ad-hoc risk analyses are necessary for this purpose. Identified risks must be systematically recorded and categorized, evaluated, and prioritized in a risk map. The risk analyses must be documented on an ongoing basis and communicated to relevant decision-makers, e.g., Purchasing or the Executive Board. In addition, there must be annual public reporting on identified risks, violations and measures taken.

Preventive measures must be anchored in supply chain processes. For example, preference can be given to unproblematic regions or industries when selecting suppliers. Minimum transparency requirements should be defined in the supplier qualification process, or contractual assurances of audits be demanded. Internally, the dual control principle and extended documentation requirements should be enforced for all contracts. It is also important to train staff in risk management and to raise awareness of ESG issues.

Gradation between a company’s own business area with its direct suppliers (Tier 1), and the indirect suppliers (Tier 2-n) is provided. Only when there is a substantiated suspicion of violations of obligations or bans (e.g., after the company has been informed by an NGO about restrictions on trade unionization at a raw material supplier), risk analysis must be actively carried out for the latter and a concept of measures drawn up. Prior to this, passive monitoring is sufficient, i.e., knowledge of all Tier 2-n suppliers and screening of publicly available data and reports to identify relevant risks. In contrast, active risk monitoring (i.e., data-based risk sensing and, depending on the priority, demanding comprehensive documentation up to and including remote and on-site audits) must be carried out on a permanent basis in the company’s own business unit and at Tier 1 suppliers. Preventive measures must be taken, and, in the event of violations, remedial measures must be implemented promptly and with a specific schedule.

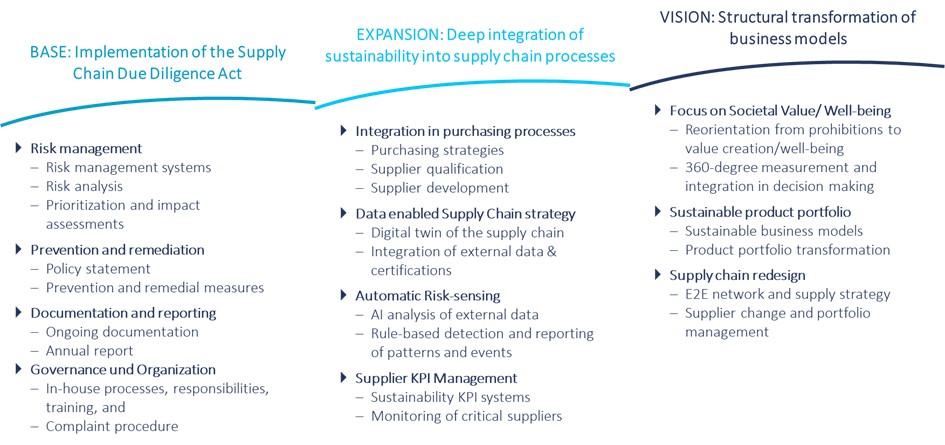

The legally compliant fulfillment of due diligence obligations poses major challenges for companies because an advanced level of transparency and control over their own supply chain is required. To meet the resulting data collection, analysis, and management efforts with a high level of quality, companies should immediately consider the next development horizon: the deep integration of sustainability into supply chain processes and the extensive, rule-based automation of risk management. Building on this, a structural transformation of business models can be initiated. Along this path, an evolution from reactive and manual monitoring of ESG risks to integration of ESG into predictive, proactive, and systems-based decision making within sustainable supply chains and business models must happen.

For many companies, compliance with due diligence requirements will only be possible with manual effort in the short term. To prevent purely reactive monitoring and administration from taking center stage, leaving limited room for structural improvement of supply chains, effective digitization and automation of supply chain mapping, risk sensing and data analysis is a basic prerequisite. The “EXPANSION” stage (Fig. 4) outlines the prerequisites that need to be implemented so that managers can focus on forward-looking decision-making processes and the strategic design of the supply chain. This begins with the definition of concrete sustainability requirements aligned with one’s own business model. The German Supply Chain Act serves as a starting point and minimum framework for this purpose.

The integration of sustainability requirements begins with purchasing strategies, as well as in the subsequent processes of supplier qualification and development. Deep improvements are achieved in today’s interconnected supply chains through intensive collaboration and by developing strategic suppliers via KPI systems. An important foundation for sustainable management is data-driven visibility across end-to-end supply chains. Integrative systems enable the construction and modelling of digital supply chain twins or ESG risk maps.

Even system-supported risk management will reach its limits at some point with the creation of transparency on Tier 2-n suppliers unless it is closely or automatically connected to external databases on supplier standards and certifications. It is thus advisable to select ESG labels or industry initiatives (e.g., Responsible Minerals Initiative, Sustainable Apparel Coalition, Better Buying) that match the company’s own requirements. Supplier relationships are aligned accordingly, and integration of external supplier data into purchasing workflows in real time is enabled. To ensure functioning management processes, adherence to recognized standards can be required from suppliers. Examples are ISO 14001 for environmental issues, ISO 9001 for quality management, ISO 20400 for sustainable procurement, SA8000 for social issues or OHSAS 18001 for occupational health and safety.

The Supply Chain Act should be taken as an opportunity to define a vision for the structural transformation of business models (Fig. 4). Supply chain strategies must be holistically aligned with the sustainability requirements increasingly being imposed by politics and society. The focus must move from mere compliance with prohibitions to active promotion of societal value creation and well-being of directly and indirectly affected stakeholders. The entire ESG spectrum (see Fig. 2) must be considered, and the effects of corporate activities must be analyzed over 360 degrees.

The fundamental and therefore most effective decisions for sustainability are made with the product portfolio. Portfolio strategy and product development therefore need to be enriched using ESG criteria (e.g., by applying circular economy concepts for resource consumption minimization to the sales models). This results in new levers for the design of the supply chain and for the active development of suppliers with a strong ESG performance.

The priority now is to implement the Supply Chain Act. However, it is worth taking a thorough approach to lay the foundations for further developments to integrate sustainability deeply into processes of end-to-end supply chain management. Companies should first use risk analyses to identify particularly relevant risk areas for their own business model. This enables them to prioritize the implementation and development of the required management processes.

It can be expected that upcoming framework conditions and laws, such as the “EU DUE Diligence Legislation” announced in March 2021, will further specify, and tighten the demands on companies. One thing is clear: the issue of social and environmental sustainability in supply chains has gained momentum, and companies need to address this field strategically and proactively: Robust implementation of risk management and reporting requirements in the Supply Chain Act must be quickly followed by deeply embedding sustainability in supply chain processes and support through technology and automation. The target focus must be gradually expanded (from minimum standards and prohibitions towards societal value creation and well-being) and translated into transformative business models and supply chain concepts.

What challenges does your company face regarding sustainable supply chains? Please give us feedback, we look forward to exchanging ideas with you: Send your e-mail to Thomas Ebel.

Learn how Agentic AI enables digital transformation, delivering true hyperautomation.

Reimagine resilience and proactively minimize supply chain risks

This article shall help you to understand how to optimize your inventory positions in a month – or even less.

Modern PLM systems empower businesses to achieve product excellence in fast-paced markets by enhancing collaboration, agility and innovation.